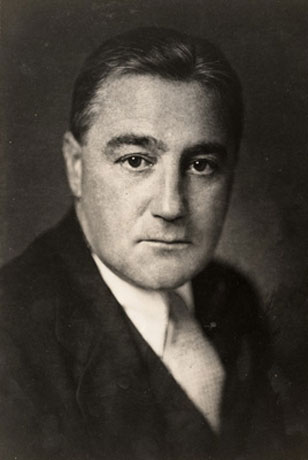

Charles Meigs Biddle Cadwalader (1885-1959)

Charles Meigs Biddle Cadwalader

Academy Archives, Coll. 457, 4828

Charles M. B. Cadwalader was the energetic Managing Director and President of the Academy of Natural Sciences between 1928 and 1951, and the visionary figure largely responsible for transforming the venerable institution into a modern center for research and education. Museum membership quintupled with Cadwalader at the helm, collections grew substantially, and he superintended the installation of the Audubon Bird Hall as well as the creation of many of the memorable habitat groups still on display today.

Cadwalader became a lifetime member of the Academy when he was only 23, and proved his knowledge and enthusiasm for natural history to trustees and staff, despite his lack of formal scientific credentials. He would eventually be granted an honorary M.S. from the University of Pennsylvania in recognition of his exemplary scientific leadership of the Academy. Although he became Academy President on the cusp of the Depression, Cadwalader did not let national economic woes dim his plans. Instead, he devoted himself to expanding the institution’s activities, successfully raising funds for new exhibitions, expeditions and public programs, and establishing a Department of Education. According to a 1937 profile in Time magazine, Cadwalader had an irresistible charm which he put to use convincing wealthy benefactors not only to contribute to the Academy’s mission but also to go specimen hunting on their own dime. The result of Cadwalader’s insistence on continued investment in the Academy was record numbers of visitors and a revitalized institution.

As a boy growing up in Fort Washington, a Philadelphia suburb, Cadwalader first visited the Academy because of his interest in birds, an enthusiasm that persisted throughout his life. It should come as no surprise that under his leadership, the Academy’s ornithology department thrived. Cadwalader was an avid, lifelong hunter whose unshakeable belief in the importance of field collecting – during a time when other institutions were turning away from the activity – helped grow the Academy’s holdings during a critical period. Thousands of the ornithology department’s most valuable specimens were added during his tenure, including M.A. Carriker and Clement Newbold’s birds of Peru, Harold King’s Sudanese waterfowl, Wharton Huber’s North American specimens, and James Bond’s collections from the West Indies. He personally helped finance the purchase of the A. Blayney Percival collection of East African Birds, the Panama Darien Expedition, M.A. Carriker’s ornithological expedition to Bolivia, and co-financed Rodolphe Meyer de Schauensee’s collecting trips to Siam and Colombia. These expeditions produced more than 15,000 specimens, including 97 type specimens. Cadwalader also contributed more than 3,000 specimens he collected himself.

Brown Tinamou

(Crypturellus obsoletus cruces)

ANSP 145833, Holotype

Cinereous Tinamou

(Crypturellus cinereus cinereus)

ANSP 119455, Holotype

The largest of the Cadwalader contibutions to the Ornithology Department is the series of specimens collected by Mel Carriker in Bolivia from 1935 to 1938. Nearly 8,000 study skins are included in this spectacular series, all beautifully prepared by Carriker, one of the greatest field ornithologists of all time. Included in the collection are type specimens for at least 74 new species of birds found during these expeditions. Some of the most remarkable include: Ash-breasted Tit Tyrant, Anairetes alpinus bolivianus (ANSP 119967), Horned Guan Crax u. unicornis (138764), several species of Tinamou, Crypturellus (one of Carriker’s favorite groups, 119455, 119473, 145833), and Green-fronted Lancebill, Doryfera l. ludovicae (120803). This wonderful collection forms a very important early record of bird life in Bolivia. Unfortunately, many of the collecting locations from these expeditions have been completely destroyed and converted to various forms of farming. Current research into the evolution of the birds of Bolivia still relies on these early Bolivian specimens. In fact, many hundred are on loan to universities right now.

Mr. Cadwalader’s contributions were not limited to specimens collected in South America by a hired collector for the Academy. An avid outdoorsman and hunter, many of the birds that Cadwalader shot ended up as Academy bird specimens as well. Of particular note are the large series of waterfowl from the east coast, in particular, from the Cadwaladers’ Waterlily Plantation in North Carolina. All of these specimens were beautifully prepared by the Academy’s own Wharton Huber, a truly great bird skinner. These duck skins have a newfound use in the modern research of climate change, as the feathers reflect a very accurate indication of climatic conditions at the time of collection.

The scion of a prominent family that traces its American roots to the century before the Revolutionary War, Cadwalader declined to take a salary during his quarter-century leading the Academy. His total lifetime donations to the Academy amount to nearly $200,000—approximately $1.5 million in today’s money—but his contributions to the ornithology department cannot possibly be monetized.

He never married and had no children but Cadwalader had a warm relationship with his niece Catherine Chambers Cadwalader Boericke, his nephew’s wife. She recalls once sitting with her uncle and mother under a live oak tree after a morning’s hunting while he mused about the vast numbers of birds and insects that had lived in or visited the old tree, that it was a whole world unto itself. He was, perhaps, secretly a Romantic

yet the Academy is indebted to him to this day for his vision, energy and superb leadership skills.